A professor of Philosophy of Science, Logic, and Critical Rationalism at Lagos State University (LASU), Oseni Afisi, has blamed the persistent intellectual crisis, identity conflicts, and cultural alienation in Africa on the dominance of Western theories and philosophies in the continent’s educational systems.

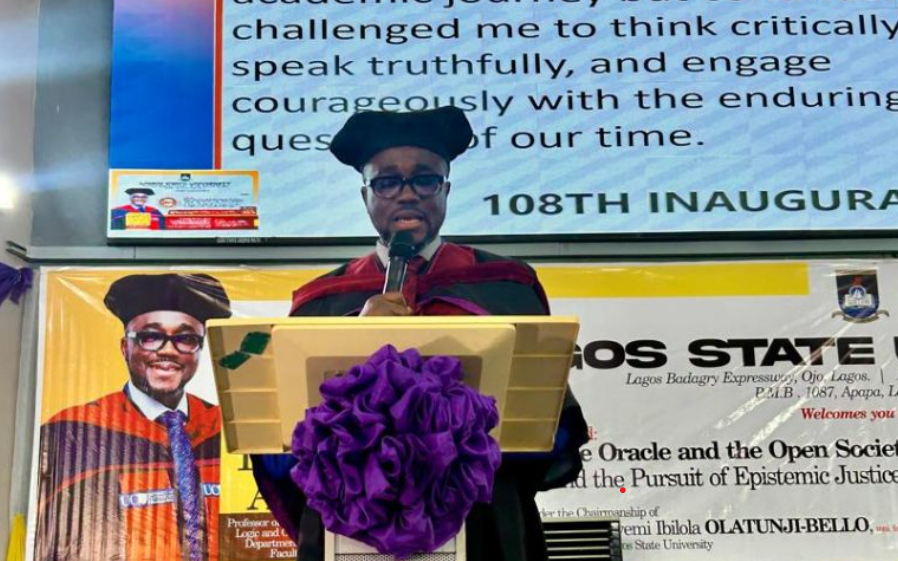

Speaking during his inaugural lecture titled “The Oracle and the Open Society: Rethinking the Evolution of Authority and the Pursuit of Epistemic Justice in African Philosophical Thought,” held on Tuesday at the LASU campus in Ojo, Afisi argued that African scholars often feel compelled to adopt foreign intellectual frameworks, leading to identity crises and conflicting value systems.

He explained that Africans are frequently torn between holding onto ancestral wisdom and conforming to Western rationality, as well as between traditional spiritual beliefs and imported religious doctrines.

“For centuries, African knowledge systems—spanning medicine, governance, philosophy, and environmental management—were systematically devalued and dismissed as mere superstition by colonial powers,” Afisi said. “European colonisers imposed their educational models, replacing indigenous wisdom with Western science, philosophy, and religion. Systems like Ifá, which are coherent and ethically grounded, were rebranded as irrational.”

He lamented that modern African schools and universities still prioritise Western philosophers, scientists, and theorists, leaving students disconnected from their cultural heritage. This intellectual dependency, he said, fosters a sense of inferiority and discourages the development of original African frameworks rooted in local realities.

Afisi warned that such dependency entrenches intellectual marginalisation and stifles innovation. “African scholars are pressured to adopt foreign theories rather than develop their own intellectual traditions,” he noted.

To tackle these challenges, he urged educators and policymakers to reform curricula across all levels of education to include African perspectives in science, logic, and ethics.

He advocated for the creation of textbooks and learning materials that promote dialogical reasoning, moral accountability, and critical thinking, all grounded in local languages, oral traditions, and community experiences.

“Curricula at all levels must move beyond token inclusion and genuinely reflect the depth, complexity, and contemporary relevance of African philosophies,” Afisi asserted.

He also called for the government to formally recognise and regulate the interface between biomedicine and traditional healing practices. Furthermore, he emphasised the importance of integrating African philosophical thought into both humanities and science education, suggesting that public intellectuals and philosophers should be appointed to policy advisory roles to promote culturally sensitive governance.

“I strongly advocate including Philosophy as part of courses taught in JUPEB and A-Level programs in Nigeria,” he added.

Afisi also raised concerns over ongoing neocolonial influences that, he said, have deepened Africa’s identity crisis and contributed to intellectual stagnation.

“One of Africa’s biggest challenges is epistemic hegemony and intellectual marginalisation,” he said. “This is closely linked to a crisis of identity and epistemic fragmentation, with African societies caught between conflicting value systems—traditional communal ethics, religious doctrines introduced by missionaries, and the secular individualism promoted by Western modernity.”

He further argued that Africa’s underdevelopment is exacerbated by political dependency and external control. Many African nations, he noted, remain economically and intellectually reliant on former colonial powers and international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

“African economies are still structured around the export of raw materials and the import of finished goods, making them vulnerable to global market shocks,” he explained. “Politically, leaders often pursue policies dictated by foreign donors instead of developing independent, context-specific strategies.”

Intellectually, he continued, African universities and research institutes heavily depend on foreign theories, often dismissing indigenous knowledge as primitive or irrelevant.

“This dependence is compounded by leadership crises and a decline in ethical values,” Afisi added. “In many African societies, leadership is tainted by corruption, nepotism, and self-interest, replacing traditional values of integrity, accountability, and communal responsibility with a culture of impunity.”